You can find Will Self’s introduction to Russell Hoban’s masterpiece, Riddley Walker, here, which has obvious parallels with Self’s The Book of Dave.

Little People In The City: The Street Art Of Slinkachu

Little People In The City – Slinkachu

![]()

![]()

See all books by Slinkachu at

Amazon.co.uk | Amazon.com

Will has written the foreword to Little People In The City: The Street Art Of Slinkachu – read on for more info.

Synopsis:

‘They’re Not Pets, Susan,’ says a stern father who has just shot a bumblebee, its wings sparkling in the evening sunlight; a lone office worker, less than an inch high, looks out over the river in his lunch break, ‘Dreaming of Packing it all In’; and a tiny couple share a ‘Last Kiss’ against the soft neon lights of the city at midnight. Mixing sharp humour with a delicious edge of melancholy, “Little People in the City” brings together the collected photographs of Slinkachu, a street-artist who for several years has been leaving little hand-painted people in the bustling city to fend for themselves, waiting to be discovered…’ Oddly enough, even when you know they are just hand-painted figurines, you can’t help but feel that their plights convey something of our own fears about being lost and vulnerable in a big, bad city.’ – “The Times”.

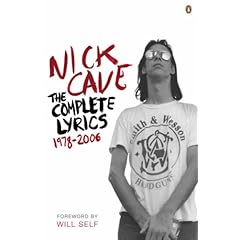

Foreword to Nick Cave: The Complete Lyrics

The Complete Lyrics – Nick Cave

![]()

![]()

See all books by

Nick Cave at

Amazon.co.uk

Amazon.com

Will Self’s Foreword to Nick Cave: The Complete Lyrics

Some 20 years ago, I had a long wrangle with the music writer Barney Hoskyns about the relative virtues of rock lyricists. Barney’s view was (and I hope I’m not traducing him in any way) that simplicity was the key. The structure of pop songs – most of which derive from the holy miscegenation of the English ballad form and the eight-bar blues – the importance to them of melody and their fairly short duration: all of these factors meant that facile rhymes, basic narratives and straightforward sentiments made for the best lyrics.

In view of this, Barney championed the writing of Smokey Robinson. Indeed, he went further, saying that Robinson was incomparably the best postwar pop lyricist. Perhaps to be contrary – or maybe because I genuinely believed it – I passionately dissented from this view, arguing that a lyricist such as Bob Dylan managed to be at once experimental and deeply poetic, while still packing a perfectly sweet pop punch to the gut.

As I recall, the argument eventually came down to a single couplet from Dylan’s song “Visions of Johanna”: “On the back of the fish truck that loads / While my conscience explodes”. Barney contended that this, in and of itself, meant absolutely nothing at all. Therefore, it could only be viewed either as a self-indulgent verbal riff, or as filler, marking time until the beat cranked up again.

Being forced to analyse the meaning of this trope was, initially, unwelcome. I had no desire either to descend into the nerdish, psycho-biographical slough of the Dylanologists or to ascend to the arid heights of those academics, who have hung on to their tenure by maintaining the view that some songwriters may be considered quite as much “poets” as their unaccompanied counterparts. So far as I’m concerned this approach has always prompted the question: if lyricists are poets, then what are poets? Presumably one-man bands without a band?

Over the past two decades, to my own satisfaction, at least, I’ve come up with not just one viable interpretation of the vexed unloading fish truck, but many. Moreover, I’ve come to an understanding of the nature and purpose of lyrics that satisfies me, while incidentally explaining the collapse of poetry as a popular art form. Nowadays, if we picture the poetic muse at all, it’s as a superannuated folkie, sitting in the corner of the literary lounge bar, holding his ear and yodelling some old bollocks or other. Whatever need we have for the esemplastic unities of sound, meaning and rhythm that were traditionally supplied by spoken verse, we now find it supplied in sung lyrics.

Curiously, it was also Hoskyns, a couple of years before, who nearly effected an introduction between me and a young Australian punk band that he was then in the process of championing. I was hanging out with a mutual friend, lost in the toxic imbroglio of those telescopic times, when the invitation came to head up to Clapham and meet the Birthday Party. We never made it. We never got our £10 party bag.

I was aware of Nick Cave, of course his incendiary performances – setting fire to the gothic catafalque above pop’s tomb, and writhing as it burned, burned, burned – were a defining part of the same, troubled era. However, I came to the music late. Indeed, I knew Nick himself, socially, long before I immersed myself in his oeuvre. Looking back on that time – the late 1980s and early 1990s – this seems staggering. I’m often reminded of the first line of Woody Allen’s parody of Albert Speer’s disingenuous memoir: “I did not know Hitler was a Nazi, for years I thought he worked for the phone company.”

I may not have thought Nick Cave worked for the phone company, but I had no conception of the extent to which his creative gestalt was shot through by harmony quite as much as semantics. He was an affable, if gaunt, bloke I saw at barbecues with his kids.

Then I read his novel And the Ass Saw the Angel and was exposed, full force, to the great Manichean divide that rives the Cave worldview. Exposed also to his very individual and mythopoeic terrain: a landscape, present in his songs and his prose alike, wherein sex kicks up the dust, murders take place in the heat (of the moment) and the sins of the fathers are visited on everyone. To those unfamiliar with the very particularity of the Australian hinterland – both physical and cultural – the backdrop to many Cave ballads, with their talk of guns, knives, horses and brides, may seem cut from a similar cloth to that of lyricists such as Johnny Cash, Dylan and the blues men and country artists they revere.

Not so. Cave’s mise en scene is as particular to his Australian patrimony as the whorls are to his fingers, or his lexicon is to his idiolect. Here, in rural Victoria, the light is harsher, the flies’ legs are moister and the blood takes longer to coagulate. A persistent atmosphere of the uncanny pervades the world the songster summons up. While immersed in a Cave lyric, it’s easy to believe not only in full temporal simultaneity – the indigenes are hacked to death, even as a football is kicked across the oval – but also that this sepia land marches with ancient Israel itself, both the Pharisees and the Kelly Gang having been clamped by the neck for the time necessary to secure a group portrait.

Cave, as a poetic craftsman, provides all the enjambment, ellipsis and onomatopoeia that anyone could wish for. A word on eroticism and the dreadful dolour of knowing not only that all passion is spent – but also that you’re overdrawn. If Cave were to be typified as a lyricist of blood, guts and angst, it would be a grave mistake. He stands as one of the great writers on love of our era. Each Cave love song is at once perfumed with yearning, and already stinks of the putrefying loss to come. For Cave, consummation is always exactly that.

I must also mention a vein of irony – satire even – that runs through Nick Cave’s lyrics. One of my personal favourites, “God Is in the House”, demonstrates his ability to ironise, then re-ironise, and then re-ironise again, engendering a dizzying vortex as received values are sucked down the pointed plughole. Arguably, such a light heavyweight touch runs counter to Cave’s espousal of the Old Testament verities, yet I prefer to acknowledge it as of a piece: Ecce homo.

So, in the last analysis, it seems that the decades-old wrangle about lyricists was quite as devoid of meaning as the unloading fish truck, for, at that very time, in the existential inner cities of London, Berlin, New York, Paris, there was tapping away a songwriter who was far more than the sum of these parts: the aching heart of Smokey, implanted in the tortured breast of Zimmerman.

Nick Cave: The Complete Lyrics is published by Penguin

Alasdair Gray – 1982, Janine

Will Self wrote an introduction for the Canongate edition of Alasdair Gray’s book.

Synopis:

An unforgettably challenging book about power and powerlessness, men and women, masters and servants, small countries and big countries, Alasdair Gray’s exploration of the politics of pornography has lost none of its power to shock. Disliked by some and praised by others, 1982 Janine is a searing portrait of male need and inadequacy, as explored via the lonely sexual fantasies of Jock McLeish, failed husband, lover and business man. Yet there is hope here, too, and the humour (if black) and the imaginative and textual energy of the narrative achieves its own kind of redemption in the end.

You can buy Janine, 1982 at Amazon.co.uk

David Shrigley – Why We Got The Sack From The Museum

David Shrigley – Why We Got The Sack From The Museum

![]()

![]()

Will Self wrote the introduction for David Shrigley’s book of drawings and observations.

From the Amazon.co.uk review: “As Will Self concedes in his introduction to Shrigley’s new book Why We Got the Sack from the Museum, it is virtually impossible to explain the crude, anarchic humour and energy of Shrigley’s drawings and observations. In fact, Shrigley’s work can hardly be described as “drawing” at all, so unusual are his child-like, line depictions and comments on the dysfunctional urban world which he sees around him. Bees with human heads refuse to land on vegetation dismissed as “crap”; Shrigley invites the reader to attach postcards to car windows informing their owners that they are in fact the result of laboratory experiments involving rat droppings; a hastily drawn cup of tea is advertised for sale, £100 or nearest offer, white with two sugars. And so the book goes on, extremely funny and playful. Its darker and more cynical moments are made even funnier, and then disturbing, by the sheer naivety of the drawings.”

William Burroughs: Junky

Penguin 2002 edition

Introduction by Will Self

Synopsis

‘Junk is not, like alcohol or a weed, a means to increased enjoyment of life. Junk is not a kick. It is a way of life.’ In this complete and unexpurgated edtion of Burroughs’ famous book, he depicts the addict’s life: his hallucinations, his ghostly noctural wanderings, his strange sexuality and his hunger for the needle. Junky remains one of the most accurate and mesmerising account of addiction ever written.

Alasdair Gray: An Introduction

[This essay appears in the British Library edition of Essays on Alasdair Gray, edited by Phil Moores. Reproduced by kind permission of the British Library. © The British Library 2002]

A letter arrives from Phil Moores whose address is listed as follows: British Library, Customer Services, Document Supply Centre, Boston Spa, Wetherby, West Yorkshire. He encloses a selection of essays about the work of the Scottish novelist, artist, poet and politico-philosophic eminence grise, Alasdair Gray. You are holding this book in your hand so you know what those essays are, but picture to yourself (and let it be a Gray illustration, all firm, flowing pen-and-ink lines, precise adumbration, colour – if at all – in smooth, monochrome blocks), my own investigation of these enclosures.

Detail 1: I sit, islanded in light from a globular steel reading lamp of fifties vintage. Around me on the purple-black floorboards are sheaves of paper, my brow is furrowed, my chin is tripled, my fingers play a chord upon my cheek.

Detail 2: I go to my spare bedroom and retrieve the copy of Gray’s novel ‘Something Leather’, that the author gave me himself. (At that time, the early nineties, Gray carried a small rucksack full of his own titles, which he offered for sale at readings. Mine is inscribed; ‘To Will Self, in memory of our outing to Cardiff’. We went to Wales by train from London, with an American performance poet called Peter Plate. My wife tells me that Plate usually likes to pack a gun, but alas, in Cardiff this was not possible. The hotel was glutinously rendered and fusty in the extreme. There may well have been diamond patterned mullions. After the three of us had given a reading – of which I remember little, saving that a Welsh poet gave me a copy of his self-published collection ‘The Stuff of Love’, good title that – Plate, Gray and I retired to the hotel and drank a lot of whisky. The bar was tiny, the hotelier obese. Either Gray, Plate and I carried the hotelier to bed, or Gray, the hotelier and I carried Plate to bed, or there was some further variation of this, or, just possibly, we all dossed down together on the floor of the bar. At any rate, we were all also up bright and early the following morning, Gray his usual self, shy, gentle, yet strident and immensely talkative. Mm.), and begin to reread it.

Detail 3: In the hallway, where the larger hardbacks are kept, I retrieve my copy of Gray’s ‘The Book of Prefaces’, sent to me by Gray’s erstwhile English publisher, Liz Calder (for reasons of Scottishness and Loyalty, Gray has been subject to publishing books alternately with Calder’s house, Bloomsbury, and Canongate. Liz Calder worships Gray as if he is a small, bespectacled, grey bearded deity. It could be that Gray is the God in Liz’s narrative. God is in all Gray’s narratives. Somewhere.)

Detail 4: In mine and my wife’s bedroom I face a wall of books and intone ‘I wonder where that copy of Lan – ‘ but then see it.

Detail 5: I have retreated, together with books and papers, to my study at the top of the house, where I write this introduction (‘introduction’ in the loosest sense, what could be more otiose than to gloss a collection of critical essays with one more?) on a flat screen monitor I bought a month ago in the Tottenham Court Road. (Toby, who used to ‘do’ my computers for me, said that it was pointless replacing the old monitor when it packed in, and that I should upgrade the whole system. Contrarily, I decided to downgrade Toby instead.)

Gray does not type himself. All these vignettes of me-writing-the-introduction are linked together by tendrils of vines, or stalks of thistles, or organs of the body, or lobes of the brain, or are poised in conch shells and skulls, alembics and crucibles, mortars and other vessels of that sort. Moores feels that: ‘It’s sad that there is still a gap for this book for a writer/artist of Alasdair’s importance: perhaps it’s because he’s Scottish, perhaps because he wasn’t young enough to grab the media’s attention like others of the 80s “Granta Young Novelists”, but whatever the reason his profile is still too low. Perhaps this book will help (but probably not).’

Hmm. Such pessimism and cynicism in one so young (and I envision Moores as young, although a Document Supply Centre is not where you would expect to find anyone who was not – at least psychically – a valetudinarian.)

Personally, I find it very easy to imagine Gray as a svelte, highly photogenic, metropolitan novelist. In the mid-nineties, when I went often up to Orkney to write, on a couple of occasions, when I was passing through Glasgow, I took Gray and his partner Morag MacAlpine out to dinner at the Ubiquitous Chip, a restaurant where Gray himself – some years before – had done murals on the walls of the staircase leading to the lavatories. Gray would strike attitudes over his Troon-landed cod, reminding me of no one much besides Anthony Blanche in Waugh’s ‘Brideshead Revisited’.

Anyway, who gives a fuck about his profile? Literary art is not a competition of any kind at all, what could it be like to win? Suffice to say, Gray is in my estimation a great writer, perhaps the greatest living in this archipelago today. Others agree. I’ve only just now looked up ‘Lanark’, his magnum opus, on the Amazon.com website (this dumb, digital, obsolete computer multi-tasks, as do Gray’s analogue fictions), the sales were respectable, the reader reviews fulsome. One said: ‘I owe my life to this book. In 1984 I was marooned in the Roehampton Limb- fitting Centre, the victim of a bizarre hit-and-run accident, whereby an out of control invalid carriage ran me over several times. The specialists all concurred that I would never walk again, even with the most advanced prostheses they had on offer. After reading ‘Lanark’ by Alasdair Gray, such was my Apprehension of a New Jerusalem, arrived at by the author’s Fulsome Humanity, tempered by the Judiciousness of his Despair, and the Percipience of his Neo-Marxist Critique of the Established Authorities, that seemingly in response to one of the novel’s own Fantastical Conceits, I found myself growing, in a matter of days, two superb, reptilian nether limbs. These have not only served me better than my own human legs as a form of locomotion, they have also made me a Sexual Commodity much in demand on the burgeoning fetish scene of the South West London suburbs.’ Any encomium I could add to this would be worse than pathetic.

Gray’s friends and collaborators are represented in this collection, as are his fans. Some essays deal with Gray’s fiction, some with his political; writing, others with his exegetical labours, and others still with his visual art. I have attempted, through this fantastical schema – part reverie, part parody, part fantasy – to suggest to you quite how important I view Gray to be. In Scotland, where the fruits of the Enlightenment are still to be found rotting on the concrete floors of deracinated orchards, Gray represents quite as much of a phenomenon as he does to those of us south of the border. However, to the Scottish, Gray is at least imaginable, whereas to the English he is barely conceivable. A creative polymath with an integrated politico-philosophic vision is not something to be sought in the native land of the hypocrite. Although, that being noted, much documentation concerning Gray’s work now reposes in Wetherby, and you have this fine volume in your hand. Treasure it. Grip it tightly.

Will Self 2002

Alisdair Gray: Critical Appreciations And A Bibliography

Edited by Phil Moores

Introduction by Will Self

[Read Will’s introduction online]

Synopsis

From “Lanark” to “The Book of Prefaces”, Alasdair Gray, more than any other writer still working, can be claimed as the modern successor to William Blake. As well as being award-winning tales, his books are also works of art, from the embossed boards to his own illustrations: books, not texts. Since “Lanark” appeared in 1981, Gray has produced work of all kinds – novels, short stories, poetry, polemic, plays – all of which retain the sense of humour, Scottish heart, intellectual curiosity and unique style that is Gray’s mark. This volume of essays contains a detailed bibliography of Gray’s writing and design, illustrations of his artwork and original essays from such diverse hands as the poet Professor Philip Hobsbaum, Kevin Williamson, author of “Drugs” and “The Party Line”, and Jonathan Coe, author of “The Rotters’ Club”. In addition, the illustrated jacket has been designed by Alasdair Gray himself, who is also contributing a personal view of his career to date.