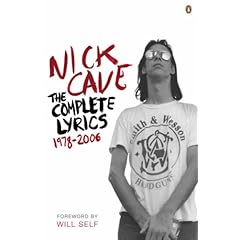

The Complete Lyrics – Nick Cave

![]()

![]()

See all books by

Nick Cave at

Amazon.co.uk

Amazon.com

Will Self’s Foreword to Nick Cave: The Complete Lyrics

Some 20 years ago, I had a long wrangle with the music writer Barney Hoskyns about the relative virtues of rock lyricists. Barney’s view was (and I hope I’m not traducing him in any way) that simplicity was the key. The structure of pop songs – most of which derive from the holy miscegenation of the English ballad form and the eight-bar blues – the importance to them of melody and their fairly short duration: all of these factors meant that facile rhymes, basic narratives and straightforward sentiments made for the best lyrics.

In view of this, Barney championed the writing of Smokey Robinson. Indeed, he went further, saying that Robinson was incomparably the best postwar pop lyricist. Perhaps to be contrary – or maybe because I genuinely believed it – I passionately dissented from this view, arguing that a lyricist such as Bob Dylan managed to be at once experimental and deeply poetic, while still packing a perfectly sweet pop punch to the gut.

As I recall, the argument eventually came down to a single couplet from Dylan’s song “Visions of Johanna”: “On the back of the fish truck that loads / While my conscience explodes”. Barney contended that this, in and of itself, meant absolutely nothing at all. Therefore, it could only be viewed either as a self-indulgent verbal riff, or as filler, marking time until the beat cranked up again.

Being forced to analyse the meaning of this trope was, initially, unwelcome. I had no desire either to descend into the nerdish, psycho-biographical slough of the Dylanologists or to ascend to the arid heights of those academics, who have hung on to their tenure by maintaining the view that some songwriters may be considered quite as much “poets” as their unaccompanied counterparts. So far as I’m concerned this approach has always prompted the question: if lyricists are poets, then what are poets? Presumably one-man bands without a band?

Over the past two decades, to my own satisfaction, at least, I’ve come up with not just one viable interpretation of the vexed unloading fish truck, but many. Moreover, I’ve come to an understanding of the nature and purpose of lyrics that satisfies me, while incidentally explaining the collapse of poetry as a popular art form. Nowadays, if we picture the poetic muse at all, it’s as a superannuated folkie, sitting in the corner of the literary lounge bar, holding his ear and yodelling some old bollocks or other. Whatever need we have for the esemplastic unities of sound, meaning and rhythm that were traditionally supplied by spoken verse, we now find it supplied in sung lyrics.

Curiously, it was also Hoskyns, a couple of years before, who nearly effected an introduction between me and a young Australian punk band that he was then in the process of championing. I was hanging out with a mutual friend, lost in the toxic imbroglio of those telescopic times, when the invitation came to head up to Clapham and meet the Birthday Party. We never made it. We never got our £10 party bag.

I was aware of Nick Cave, of course his incendiary performances – setting fire to the gothic catafalque above pop’s tomb, and writhing as it burned, burned, burned – were a defining part of the same, troubled era. However, I came to the music late. Indeed, I knew Nick himself, socially, long before I immersed myself in his oeuvre. Looking back on that time – the late 1980s and early 1990s – this seems staggering. I’m often reminded of the first line of Woody Allen’s parody of Albert Speer’s disingenuous memoir: “I did not know Hitler was a Nazi, for years I thought he worked for the phone company.”

I may not have thought Nick Cave worked for the phone company, but I had no conception of the extent to which his creative gestalt was shot through by harmony quite as much as semantics. He was an affable, if gaunt, bloke I saw at barbecues with his kids.

Then I read his novel And the Ass Saw the Angel and was exposed, full force, to the great Manichean divide that rives the Cave worldview. Exposed also to his very individual and mythopoeic terrain: a landscape, present in his songs and his prose alike, wherein sex kicks up the dust, murders take place in the heat (of the moment) and the sins of the fathers are visited on everyone. To those unfamiliar with the very particularity of the Australian hinterland – both physical and cultural – the backdrop to many Cave ballads, with their talk of guns, knives, horses and brides, may seem cut from a similar cloth to that of lyricists such as Johnny Cash, Dylan and the blues men and country artists they revere.

Not so. Cave’s mise en scene is as particular to his Australian patrimony as the whorls are to his fingers, or his lexicon is to his idiolect. Here, in rural Victoria, the light is harsher, the flies’ legs are moister and the blood takes longer to coagulate. A persistent atmosphere of the uncanny pervades the world the songster summons up. While immersed in a Cave lyric, it’s easy to believe not only in full temporal simultaneity – the indigenes are hacked to death, even as a football is kicked across the oval – but also that this sepia land marches with ancient Israel itself, both the Pharisees and the Kelly Gang having been clamped by the neck for the time necessary to secure a group portrait.

Cave, as a poetic craftsman, provides all the enjambment, ellipsis and onomatopoeia that anyone could wish for. A word on eroticism and the dreadful dolour of knowing not only that all passion is spent – but also that you’re overdrawn. If Cave were to be typified as a lyricist of blood, guts and angst, it would be a grave mistake. He stands as one of the great writers on love of our era. Each Cave love song is at once perfumed with yearning, and already stinks of the putrefying loss to come. For Cave, consummation is always exactly that.

I must also mention a vein of irony – satire even – that runs through Nick Cave’s lyrics. One of my personal favourites, “God Is in the House”, demonstrates his ability to ironise, then re-ironise, and then re-ironise again, engendering a dizzying vortex as received values are sucked down the pointed plughole. Arguably, such a light heavyweight touch runs counter to Cave’s espousal of the Old Testament verities, yet I prefer to acknowledge it as of a piece: Ecce homo.

So, in the last analysis, it seems that the decades-old wrangle about lyricists was quite as devoid of meaning as the unloading fish truck, for, at that very time, in the existential inner cities of London, Berlin, New York, Paris, there was tapping away a songwriter who was far more than the sum of these parts: the aching heart of Smokey, implanted in the tortured breast of Zimmerman.

Nick Cave: The Complete Lyrics is published by Penguin