of The Butt can be found here

The Wisdom of Whores: Bureaucrats, Brothels and the Business of Aids by Elizabeth Pisani

Back in 1985 I was an inpatient at a drug rehab in the West Country and had genital warts that required regular and painful treatments.

Each week I went to the STD clinic at the nearby hospital, where a middle-aged consultant applied an acidic preparation to the glans of my penis. One day, while he was actually holding the afflicted portion, he remarked — quite casually — that the best way to rid the country of HIV/Aids would be to “castrate all you junkies — and the queers, too”.

You didn’t need to have a well-developed persecution complex — which I did, anyway — not to find this a little aggressive.

At the time, Aids was the nasty new kid on the infectious diseases block; the first few cases had appeared in England, but those of us in the high-risk groups could already see the battle lines being drawn across the Atlantic: the blameless sheep with “good” Aids — haemophiliacs, faithful heterosexual partners — being sectioned off from those with “bad” Aids — gay men, IV drug users, prostitutes — and the field day that the so-called “moral majority” were having.

I’d already been tested for Aids a year earlier when I’d been in hospital and, so far as I knew, I was HIV negative. Perhaps because of some early hard-drubbing into me of the basic facts about hygiene, or possibly because — in this aspect of my malady, at least — I was less chaotic than my peers, I was never a big sharer of needles. Needless to say, although I can only think of two or three occasions when I did so, of the five other people involved, two are now dead, while the other three may not have Aids but did contract the almost as nasty hepatitis C.

Elizabeth Pisani’s thoughtful and necessary book, at some length, and by following her own picaresque journey through the international Aids prevention industry, explains the evolved consequences of experiences I’ve limned in above. The message of her book is simple: no matter how much money the global community (another priceless oxymoron) chooses to throw at stopping this killer disease, entrenched attitudes — and practices — will ensure that the spectre of “slim”, as it’s known in sub-Saharan Africa, just keeps getting fatter and fatter, as the virus gorges on human life.

When Pisani — a journalist initially — became interested in epidemiology, qualified, then began working in the Aids field, the big battle was to secure funding for prevention campaigns. In part because of the chronic wonkery of the UN, in part because of the activism of the US gay community — vital as it was at the time — but mostly because of the practices that spread the disease, and their unacceptability to the Jerry Falwells of this world (and, presumably, the next), the most obvious and practicable ways of stemming the epidemic were neglected.

Instead we were given campaigns like the Thatcher government’s countrywide mailshot, warning maiden aunts in the Cotswolds not to “die of ignorance”, when the truth was that if public health had been managed effectively, they could’ve died happily ignorant of what Aids was at all. Apart from in sub-Saharan Africa — where, as Pisani plainly states, sexual mores have allowed for rapid transmission through the heterosexual population — your chances of contracting HIV/Aids remain small, unless you are an IV drug user, a prostitute or engage in anal sex.

But as Aids, because of the African epidemic, moved up the agenda of righteousness, and precisely those “moralists” who were happy for whores, queers and junkies to be shovelled out with the rest of the trash seized upon the new “good” sufferers as worthy aid recipients, so their entrenched attitudes ensured that their efforts were as useless as a condom that looks like a colander — because condoms is where it’s all at; condoms and clean needles. US government aid is not only tied to programmes that Bush and his fundamentalist backers approve of, but the recipient governments and NGOs must spend that money on anti-retroviral drugs, needles and condoms made in America.

As Pisani so elegantly establishes, this is the public health equivalent of burning taxpayers’ money in a brazier and magically expecting people on the other side of the world not to contract the virus.

It is, though, only the most glaring example of the waste, profligacy and wrong-headedness that undermines the worldwide effort to curtail a disease the transmission of which is — compared with TB, or cholera, or flu for that matter — relatively easily to guard against.

Pisani’s training as an epidemiologist leads her to commonsense conclusions — which is not to dismiss the hard, committed work she did establishing HIV/Aids prevalence across Asia, or campaigning for funding to fight its spread.

Nevertheless, it turns out that the consultant burning my warts and talking eugenics was on the money all along. He may not have expressed himself sensitively or humanely, but completely curtailing the sexual — and injecting — activity of gay men, drug users and prostitutes would certainly put the mockers on the epidemic; short of that, there are free condoms — with incentives to use them — and free sterile needles.

You can feel Pisani’s frustration as she details the idiotic lengths politicians will go to in order not to be seen to endorse the practices that pass the virus on. The provision of needle exchanges in British prisons is one obvious way of stopping them being Aids factories — and a complete political no-no.

But, I ask Pisani, weren’t things ever thus? When it comes to Aids, polio or diphtheria are not the relevant comparisons — it’s syphilis. Nothing is rational when it comes to sex, and everything really goes tits-ups when you throw drugs into the mix. Pisani isn’t exactly jolly-hockey-sticks but she’s still a ewe when it comes to Aids; unfortunately, it was already clear back in the mid-1980s, to those of us who were in high-risk groups, that this is a ram’s world.

The Wisdom of Whores is published by Granta at £17.99

01.05.08

Olympic hurdles

Read Will’s latest Psychogeography column here

10.05.08

Book panel with Simon Mayo

To listen to Will talking about The Butt on Simon Mayo’s Radio 5 Live programme on April 24 2008, sign up to the podcast.

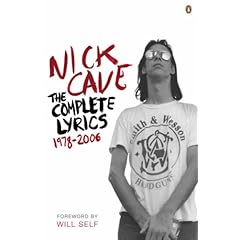

Foreword to Nick Cave: The Complete Lyrics

The Complete Lyrics – Nick Cave

![]()

![]()

See all books by

Nick Cave at

Amazon.co.uk

Amazon.com

Will Self’s Foreword to Nick Cave: The Complete Lyrics

Some 20 years ago, I had a long wrangle with the music writer Barney Hoskyns about the relative virtues of rock lyricists. Barney’s view was (and I hope I’m not traducing him in any way) that simplicity was the key. The structure of pop songs – most of which derive from the holy miscegenation of the English ballad form and the eight-bar blues – the importance to them of melody and their fairly short duration: all of these factors meant that facile rhymes, basic narratives and straightforward sentiments made for the best lyrics.

In view of this, Barney championed the writing of Smokey Robinson. Indeed, he went further, saying that Robinson was incomparably the best postwar pop lyricist. Perhaps to be contrary – or maybe because I genuinely believed it – I passionately dissented from this view, arguing that a lyricist such as Bob Dylan managed to be at once experimental and deeply poetic, while still packing a perfectly sweet pop punch to the gut.

As I recall, the argument eventually came down to a single couplet from Dylan’s song “Visions of Johanna”: “On the back of the fish truck that loads / While my conscience explodes”. Barney contended that this, in and of itself, meant absolutely nothing at all. Therefore, it could only be viewed either as a self-indulgent verbal riff, or as filler, marking time until the beat cranked up again.

Being forced to analyse the meaning of this trope was, initially, unwelcome. I had no desire either to descend into the nerdish, psycho-biographical slough of the Dylanologists or to ascend to the arid heights of those academics, who have hung on to their tenure by maintaining the view that some songwriters may be considered quite as much “poets” as their unaccompanied counterparts. So far as I’m concerned this approach has always prompted the question: if lyricists are poets, then what are poets? Presumably one-man bands without a band?

Over the past two decades, to my own satisfaction, at least, I’ve come up with not just one viable interpretation of the vexed unloading fish truck, but many. Moreover, I’ve come to an understanding of the nature and purpose of lyrics that satisfies me, while incidentally explaining the collapse of poetry as a popular art form. Nowadays, if we picture the poetic muse at all, it’s as a superannuated folkie, sitting in the corner of the literary lounge bar, holding his ear and yodelling some old bollocks or other. Whatever need we have for the esemplastic unities of sound, meaning and rhythm that were traditionally supplied by spoken verse, we now find it supplied in sung lyrics.

Curiously, it was also Hoskyns, a couple of years before, who nearly effected an introduction between me and a young Australian punk band that he was then in the process of championing. I was hanging out with a mutual friend, lost in the toxic imbroglio of those telescopic times, when the invitation came to head up to Clapham and meet the Birthday Party. We never made it. We never got our £10 party bag.

I was aware of Nick Cave, of course his incendiary performances – setting fire to the gothic catafalque above pop’s tomb, and writhing as it burned, burned, burned – were a defining part of the same, troubled era. However, I came to the music late. Indeed, I knew Nick himself, socially, long before I immersed myself in his oeuvre. Looking back on that time – the late 1980s and early 1990s – this seems staggering. I’m often reminded of the first line of Woody Allen’s parody of Albert Speer’s disingenuous memoir: “I did not know Hitler was a Nazi, for years I thought he worked for the phone company.”

I may not have thought Nick Cave worked for the phone company, but I had no conception of the extent to which his creative gestalt was shot through by harmony quite as much as semantics. He was an affable, if gaunt, bloke I saw at barbecues with his kids.

Then I read his novel And the Ass Saw the Angel and was exposed, full force, to the great Manichean divide that rives the Cave worldview. Exposed also to his very individual and mythopoeic terrain: a landscape, present in his songs and his prose alike, wherein sex kicks up the dust, murders take place in the heat (of the moment) and the sins of the fathers are visited on everyone. To those unfamiliar with the very particularity of the Australian hinterland – both physical and cultural – the backdrop to many Cave ballads, with their talk of guns, knives, horses and brides, may seem cut from a similar cloth to that of lyricists such as Johnny Cash, Dylan and the blues men and country artists they revere.

Not so. Cave’s mise en scene is as particular to his Australian patrimony as the whorls are to his fingers, or his lexicon is to his idiolect. Here, in rural Victoria, the light is harsher, the flies’ legs are moister and the blood takes longer to coagulate. A persistent atmosphere of the uncanny pervades the world the songster summons up. While immersed in a Cave lyric, it’s easy to believe not only in full temporal simultaneity – the indigenes are hacked to death, even as a football is kicked across the oval – but also that this sepia land marches with ancient Israel itself, both the Pharisees and the Kelly Gang having been clamped by the neck for the time necessary to secure a group portrait.

Cave, as a poetic craftsman, provides all the enjambment, ellipsis and onomatopoeia that anyone could wish for. A word on eroticism and the dreadful dolour of knowing not only that all passion is spent – but also that you’re overdrawn. If Cave were to be typified as a lyricist of blood, guts and angst, it would be a grave mistake. He stands as one of the great writers on love of our era. Each Cave love song is at once perfumed with yearning, and already stinks of the putrefying loss to come. For Cave, consummation is always exactly that.

I must also mention a vein of irony – satire even – that runs through Nick Cave’s lyrics. One of my personal favourites, “God Is in the House”, demonstrates his ability to ironise, then re-ironise, and then re-ironise again, engendering a dizzying vortex as received values are sucked down the pointed plughole. Arguably, such a light heavyweight touch runs counter to Cave’s espousal of the Old Testament verities, yet I prefer to acknowledge it as of a piece: Ecce homo.

So, in the last analysis, it seems that the decades-old wrangle about lyricists was quite as devoid of meaning as the unloading fish truck, for, at that very time, in the existential inner cities of London, Berlin, New York, Paris, there was tapping away a songwriter who was far more than the sum of these parts: the aching heart of Smokey, implanted in the tortured breast of Zimmerman.

Nick Cave: The Complete Lyrics is published by Penguin

‘I used to love driving … ‘

This week, Will writes about how he overcame his motoring addiction

29.04.08

Dammit, Thanet!

To Broadstairs, not to bathe – it being April – but merely take the air. The Isle of Thanet has always been a little problematic for me; I can’t even say it without recalling Ian Dury’s lines: ‘I rendezvoused with Janet / Quite near the Isle of Thanet / She looked just like a gannet … ‘ &c. Somehow the great bard of the Kilburn High Road perfectly summed up this, the very coccyx of Britain, with its seafowl and its foul maidens.

Of course, seldom has anywhere more gentrified become more chavvy. Dickens, a habitué of the town, has one of his characters in The Pickwick Papers almost expire with relief once she reaches the haven of the Albion Hotel in Broadstairs, having had to endure the day-tripping of Margate en route. Dickens wrote to a friend of the town, that “[It] was and is, and to the best of my belief will always be, the chosen resort and retreat of jaded intellectuals and exhausted nature; being, as this Deponent further saith it is, far removed from the sights and noises of the busy world, and filled with the delicious murmur and repose of the broad ocean.”

He eventually bought the misnamed Bleak House, which still stands above the little horseshoe bay, looking not remotely grim, but more like a castellated Victorian fantasia on chivalric domesticity. What, I wonder, would he make of the town now, perfused as it is with tracksuited, gel-haired denizens of Margate and Ramsgate? Indeed, the whole of this coast feels like some suburb of outer East London, so full is it of the sights and noises of the busy world.

The sandy bay that is the town’s focus remains, girded by white cliffs of chalk and terraced houses, complete with micro-interwar pleasure gardens and a lift down to the beach that looks like an off-whitewashed crematorium chimney. There’s Morrelli’s, the beautifully preserved 1950s gelateria, where you can get Jammie Dodger sundaes, and glass mugs of vaguely caffeinated froth, then consume them under a bizarre oil painting of a flooded Venice – the water creeping up over St Mark’s. These are good things, and up the steep High Street there are chip shops and charity shops and Doyle’s Psychic Emporium (“Open Your Mind”), and a sweet shop selling orange crystals, spearmint pips and liquorice wheels. There’s even an optician’s trading under the name of See Well.

We hung out on the beach, fetching teas from the Chill Time café. One ageing hopeful came metal-detecting along the strand, Dr Who gadget held out in front of him, nuzzling the sand. Then another came up along, his gaze fixed on the gritty mother lode, his headphones clamped over his cartilaginous ears. Disaster! One metal detector detected the other, and one treasure seeker grabbed for the other’s wand. A vicious mêlée ensued as the two men fought for the right to possess these found objects. The kids and I sat in the beach hut and laughed like gannets.

A happy scene, but come nightfall and the profile tyres began to screech on the tarmac, and the darkness was full of harsher, more discordant cries. I took the dog for a walk in the local park. The blackout was complete, but I was aware of the presence of many others. In any large city these might have been furtive seekers after fleeting, anonymous congress, but here, in Broadstairs, they turned out to be enormous gaggles of teenagers, wheeling around on the mown grass, their mobile phones held under their chins so that the wan uplight weirdly illuminated their vestigial features. As I grew closer to one of these gaggles I became aware of an insistent and peculiar gobbling noise; the sound of many breaking voices intoning “Fuck off, fuck off, fuck off” over and over again.

I blame Hengist and Horsa for Broadstairs’ current fall from gentility. The two Danes – or, possibly, Germans – were invited by King Vortigern of Kent to come here in the fifth century: an early form of economic migration. Fifteen hundred years later, in 1949, the anniversary of their arrival was commemorated by some latter-day pseudo-Vikings: Danish oarsmen who completed the voyage in a replica boat. They landed on the sands below Dickens’ Bleak House, and the local municipality laid on a slap-up feed of hot soup, cold poultry, and potatoes with fresh salad in ample portions. Later there was heavy-footed dancing to the accompaniment of Joseph Muscant’s salon orchestra.

But, not content with such a welcome, the town councillors foolishly changed the name of Main Bay to Viking Bay. Doubtless they thought this would cement Anglo-Danish relations, but so far as I can see the main upshot has been that the town’s inhabitants go berserk from time to time. Waiting for the train back to London, I overheard two Thanet warriors discoursing on the platform: “‘E’s a cunt inne?” said one, “always bum-licking, but if you turns yer back on ‘im ‘e’ll give you a smack in the mouf.” They were drinking Stella Artois; if only it were reassuringly expensive.

To view Ralph Steadman’s artwork, visit here

26.04.08

Will and Ralph, united at last

For those of you frustrated by the absence of Ralph Steadman’s artwork when we publish Will’s Psychogeography columns from the Independent, here at last is an archive of them.

The Never-Ending Tour #4: The curate’s egging on

A children’s TV presenter had hanged himself at Paddington Station and his body wasn’t found for six days. Grim, but then big city rail terminuses always are: the temporary repositories of vice and despair; gutters through which the pure waters of the provinces are sluiced into the urban cesspit. Paddington isn’t helped by being within yards of St Mary’s Hospital, where, in the 1890s, heroin was synthesised for the first time. The station always has this peculiar smacklight: diffuse, dreamy, brown, and desperate. In my 1993 story Design Faults in the Volvo 760 Turbo, the adulterous lovers rendezvous close to Paddington, at Sussex Gardens. The antihero parks the eponymous Volvo by the needle exchange Portakabin on South Wharf Road. A woman has written into the site, apropos of this blog, and asks is there any part of my life that is unobserved, unrecorded? All I can say in reply – paternalistically, patronisingly, and now, illegally – is that you don’t know one half of one half of one ten-thousandth of it, love.

So, five cookies for £2.99 from Millies (three milk chocolate, two white chocolate and lemon – if you’re asking), and then the 16.30 to Bath Spa. In Bath, I ate at Waggaponytail, with all the other little pink-lip-glossed Tamsins and Georgies, oh, a girl like me loves a noodle bar, so she does. One gripe: the green tea was the temperature of dishwater. What is it with me and tea nowadays? It does arouse the most fearful indignation in me, the way that on the trains they now hand you a cup of hot – not boiling water – and then the tea bag. Am I the only one, or is this a disgusting approximation of the national beverage, dictated to us by the Health & Safety ninnies?

I digress.

Topping’s bookshop in Bath is owned and run by the redoubtable Robert Topping, who was exiled from Waterstone’s in Deansgate after protesting at the introduction of central buying. His two shops – in Bath and Ely – are everything good independents should be: home and welcoming, staffed by erudite and engaging booksellers. Last time I read there, I had people stretching away to either end of the shop, so had to perorate in the round. This time they’d thoughtfully enlisted the local church, St Michael’s-Without-Bath.

The curate was most keen that I not feel restrained within the sacred precincts from delivering my homily wholly unexpurgated. However, there was a quid pro quo: he would lead the extempore congregation in a small prayer before I began. I had no objection at all – after all, it was his gaff, and I’m a militant agnostic. Moreover, as he appealed to his Lord to aid and assist my creativity, I felt a great surge of scurrilousness building up in me, and became convinced that my satirical weapons were being mightily honed. Who knows, I may yet become a regular communicant.

The never-ending tour #3: The brilliance of the Brompton

I’m not sure if sauntering up the road to Clapham Books counts as ‘touring’, but what the hell. Ed, Nikki and Al are lovely, gentle people, who took over the lease of the bookshop where they once worked and are now doing their level best to make it work in difficult times. Clapham Books is my local bookshop – not, you understand, that I live in Clapham – that would be hell. I say they’re lovely gentle people, but frankly, have you ever met a bookseller who wasn’t? I mean, they can be introverted and cantankerous in my experience, but they’re seldom aggressive, and never psychopathic.

Anyway, I read from the book, took some questions, then went off with my old mucker Nick Lezard, the critic, and my dad’s old friend the Reverend Colin MacGregor, for a meal at the Maharani across the road. The last time I ate there was in 1985 with the conga player from Kid Creole and the Coconuts, who was called something asinine like Coti Mundi. Why? Who the hell knows. The Coconuts may be long gone, but the Maharani is exactly the same: a still, brown eye at the centre of the world’s heliotrope vortex.

Then, on Saturday morning, I unfolded the Brompton, cycled to King’s Cross, folded it up again and put it – and me – on the train to Cambridge. The folding bike is perfect for this kind of day. After the Cambridge gig – organised by a very nice woman, Jo Browning Wroe, who was one of WG Sebald’s students at UEA, and attended the seminar he conducted immediately before his tragic death – I cycled back to the station, trained it to London, cycled from King’s Cross to Paddington, then trained it all the way to Swansea, where an equally nice man, Matt (Neil Morrisey’s partner in his Dylan Thomas-themed hotels and restaurants), drove me to the gig in Laugharne.

After the gig, I put the Brompton in the boot of a hire car and drove back to London, dropped the car at the hire place on the Kennington Road, unfolded the bike and prepared to cycle home through black 4am rain. Only to discover that the clip that holds the frame together had been worked free from the Brompton by my speedy passage the length of the M4 and was now locked in the boot of the hire car. But, such is the brilliance of the Brompton’s design, that by pulling hard on the handlebars I was still able to propel myself along.

What I’m trying to tell you here is sod the gigs – the biking was great.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 121

- 122

- 123

- 124

- 125

- …

- 145

- Next Page »